Share this post

Different intermittent fasting strategies, and how eating outside of “normal” eating hours can adversely affect health

In this two-part series, Dr. Michael Brown, ND, takes a comprehensive look at this popular and trending approach to a healthier lifestyle. In Part I, a look at the different approaches to intermittent fasting and how nighttime eating can adversely affect health. In Part 2, Dr. Brown takes a closer look at the clinical studies surrounding intermittent fasting, as well as those comparing this dietary strategy with caloric-restriction diets.

Traditionally, fasting has predominantly been associated with religious and spiritual practices,[1],[2],leading many to assume fasting inherently entails very restricted eating or no food whatsoever for days or weeks at a time. What most don’t realize is that fasting is actually something that the majority of us partake in every night when going to bed. “Breakfast”, being the first meal of the day, actually refers to breaking the fasting period of the previous night. Fasting during this time, which usually ranges from about six to 12 hours, falls into line with our natural circadian rhythms and the rising and setting sun, which we know very much impacts our physiology and metabolism.[3]

Intermittent fasting: a modern version of an age-old tradition

Although there are a variety of ways one can fast, a newer phenomenon trending in the health and fitness world is referred to as intermittent fasting (IF), piquing the interest of not only health enthusiasts, but the scientific community as well. A quick Google search using the term “intermittent fasting” produces an astounding 55,200,000 results! This form of fasting is achieved by ingesting minimal or zero amounts of food and caloric beverages for periods of time typically ranging from 12 hours to several days.[2] IF is distinct from caloric restriction diets in which the daily caloric intake is reduced chronically by 20 to 40%, but meal frequency is maintained.

Although there are a variety of ways one can fast, a newer phenomenon trending in the health and fitness world is referred to as intermittent fasting (IF).

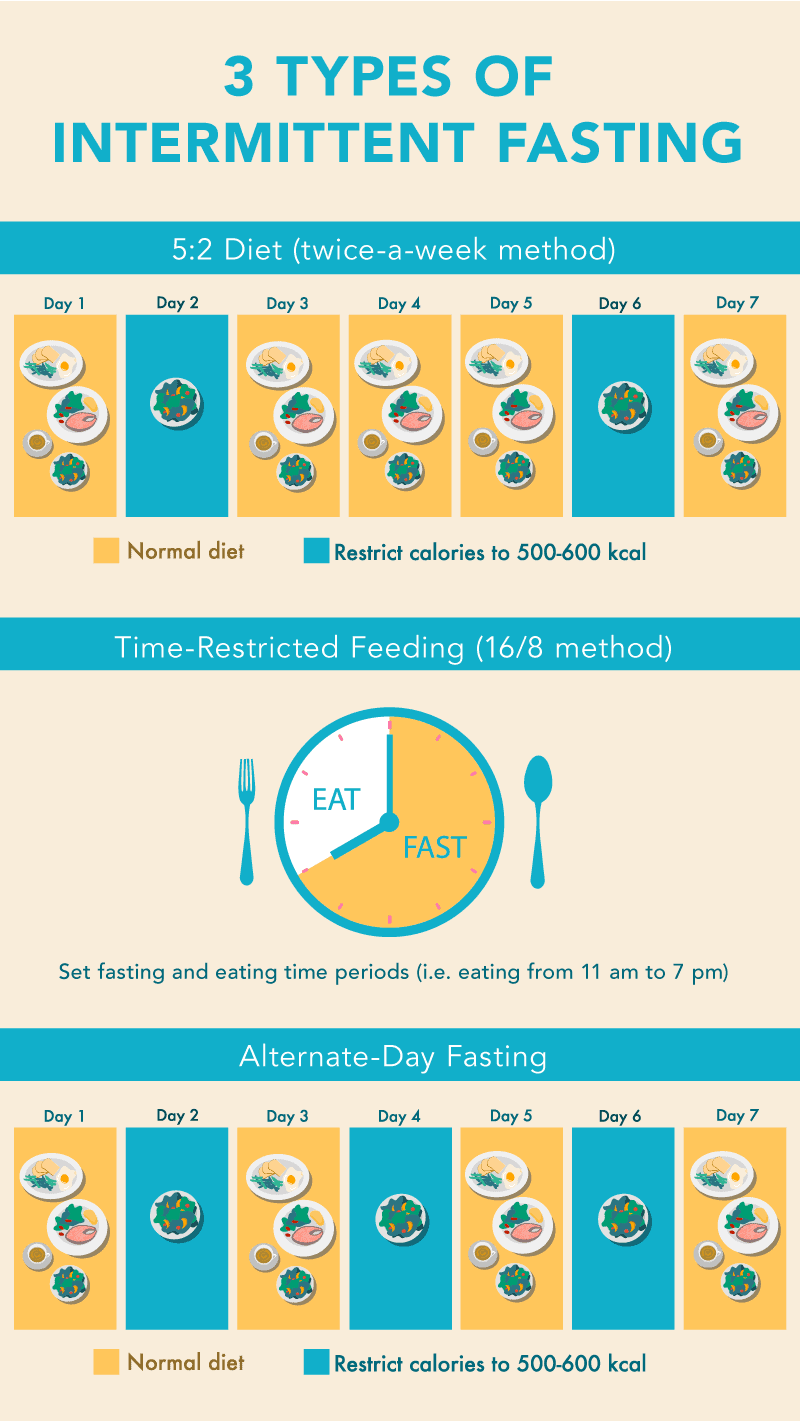

Of the various forms of IF, three of the more popular and studied variations are as follows:

- Alternate-day fasting: This form of fasting involves modified fasting every other day. For example, limiting your calories on fasting days from zero up to 500 calories (or a maximum caloric consumption of approximately 25% of your normal intake). On non-fasting days, you would resume a regular, healthy diet.[1],[4]

- Time-restricted feeding: In this option, you have set fasting and eating time periods. A very popular approach is the 16/8 method where you only eat between 11 am and 7 pm or noon and 8 pm. This method can be repeated several times per week and is popular due to easier compliance given a majority of your fasting occurs overnight.[1],[2],[3]

- Twice-a-week method: This is also called the 5:2 diet because five days of the week are normal eating days, while the other two restrict calories to 500 to 600 calories per day. For five days per week, you eat a regular, healthy diet. Then, on the other two days, you reduce your calorie intake to a quarter of your daily needs. You can choose whichever two days of the week you prefer, as long as there is at least one non-fasting day in between them.[5],[6],[7]

Circadian rhythms, eating patterns, and their impact on health

A circadian rhythm is a natural, internal process that regulates the sleep-wake cycle and many other physiological processes.[3],[8] It repeats roughly every 24 hours, being sensitive not only to light and darkness but also other cues, known as zeitgebers, such as temperature and social interactions. Most living organisms, including humans, have evolved internal metabolic mechanisms that allow them to anticipate and prepare for activity, sleep, and food intake at a specific time of day.

Both food ingestion and fasting can alter our metabolic processes. Consuming calories outside the normal eating hours (i.e., late night eating in humans) may negatively impact circadian rhythms and associated cardiometabolic parameters.[3],[8]It has been demonstrated that shift-work is associated with nighttime eating and increased risks of obesity,[9] diabetes,[10] cardiovascular disease[11], and cancer (particularly breast cancer).[12],[13],[14],[15],[16] Data from trials and prospective cohort studies also support the idea that consuming the majority of calories earlier in the day, thus prolonging the night-time fasting state (with little or no food), is associated with lower weight and improved health.[17],[18],[19],[20],[21]

Data from trials and prospective cohort studies also support the idea that consuming the majority of calories earlier in the day, thus prolonging the night-time fasting state (with little or no food), is associated with lower weight and improved health.

This data is in line with animal studies demonstrating that restricting caloric intake to an eight to 12 hour window helps support natural circadian rhythm and is associated with reduced adiposity, elevated lean muscle mass, longer sleep duration, increased endurance, reduced systemic inflammation, gut homeostasis, and improvement in other clinical biomarkers.[22],[23],[24],[25],[26]

Clearly, these studies suggest that the time during a 24-hour period in which we are eating has an impact on our health. Stay tuned for Part 2, in which we take a look at the clinical studies investigating the impact that IF has on health, as well as studies comparing it to caloric-restriction diets.

Click here to see References[1] Patterson R, Sears D. Metabolic effects of intermittent fasting. Annu Rev Nutr. 2017 Aug 21;37:371-93.

[2] Longo V, Mattson M. Fasting: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Cell Metab. 2014 Feb 4;19:181-92.

[3] Longo V, Panda S. Fasting, circadian rhythms, and time-restricted feeding in healthy lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016 Jun 14;23:1048-59.

[4] Varady K, Hellerstein M. Alternate-day fasting and chronic disease prevention: a review of human and clinical trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:7-13.

[5] Mattson M, et al. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res Rev 2017 Oct;39:46-58.

[6] Cioffi I, et al. Intermittent versus continuous energy restriction on weight loss and cardiometabolic outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Transl Med. 2018;16:371.

[7] Headland M, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intermittent energy restriction trials lasting a minimum of 6 months. Nutrients 2016 Jun;8(6):354.

[8] Rosenwasser A, Turek F. Neurobiology of circadian rhythm regulation. Sleep Med Clin. 2015 Dec;10(4):403-12.

[9] Sun, M, et al. Meta-analysis on shift work and risks of specific obesity types.

[10] Knutsson A, Kempe A. Shift work and diabetes–a systematic review. Chronobiol Int. 2014 Dec;31(10):1146-51.

[11] Torquati L, et al. Shift work and the risk of cardiovascular disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis including dose-response relationship. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2018 May 1;44(3):229-38.

[12] Grundy A, et al. Increased risk of breast cancer associated with long-term shift work in Canada. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:831-8. Obes Rev. 2018 Jan;19(1):28-40.

[13] Savvidis C, Koutsilieris M. Circadian rhythm disruption in cancer biology. Mol Med. 2012;18:1249-60.

[14] Stevens R, et al. Meeting report: the role of environmental lighting and circadian disruption in cancer and other diseases. Environ health Perpect. 2007;115:1357-62.

[15] Stevens R, Rea M. Light in the built environment: potential role of circadian disruption in endocrine disruption and breast cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2001;12:279-87.

[16] Straif K, et al. Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:1065-6.

[17] Bo S, et al. Consuming more of daily caloric intake at dinner predisposes to obesity: a 6-year prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014 Sep 24;9(9):e108467.

[18] Cahill L, et al. Prospective study of breakfast eating and incident coronary heart disease in a cohort of male US health professionals. Circulation. 2013;128:337-43.

[19] Jakubowicz D, et al. High caloric intake at breakfast versus dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity. 2013;21:2504-12.

[20] Qin L, et al. The effects of nocturnal life on endocrine circadian patterns in healthy adults. Life Sci. 2003;73:2467-75.

[21] Vander JS. Night eating syndrome: a critical review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:49-59.

[22] Chaix A, et al. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab. 2014;20:991-1005.

[23] Gill S, et al. Time-restricted feeding attenuates age-related cardiac decline in Drosophila. Science. 2015;347:1265-69.

[24] Hatorie M, et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2012;15:848-60.

[25] Sherman H. et al. Timed high-fat diet resets circadian metabolism and prevents obesity. FASEB J. 2012;26:3493-502.

[26] Zarrinpar A. et al. Diet and feeding pattern affect the diurnal dynamics of the gut microbiome. Cell Metab. 2014;20:1006-17.

[27] Longo V, Panda S. Fasting, circadian rhythms, and time-restricted feeding in healthy lifespan. Cell Metab. 2016 Jun 14;23:1048-59.

[28] Patterson R, Sears D. Metabolic effects of intermittent fasting. Annu Rev Nutr. 2017 Aug 21;37:371-93.

[29] Gill S, Panda S. A smartphone app reveals erratic diurnal eating patterns in humans that can be modulated for health benefits. Cell Metab. 2015 Nov 3;22(5):789-98.

[30] Headland M, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systemic review and meta-analysis of intermittent energy restriction trials lasting a minimum of 6 months. Nutrients. 2016 Jun;8(6):354.

[31] Arguin H, et al. Short- and long-term effects of continuous versus intermittent restrictive diet approaches on body composition and the metabolic profile in overweight and obese postmenopausal women: a pilot study. Menopause. 2012;19:870-6.

[32] Ash S, et al. Effect of intensive dietetic interventions on weight and glycemic control in overweight men with type II diabetes: a randomized trial. Int J Obes. 2003;27:797-802.

[33] Keogh J, et al. Effects of intermittent compared to continuous energy restriction on short-term weight loss and long-term weight loss maintenance. Clin Obes. 2014;4:150-6.

[34] Lantz H, et al. Intermittent versus on-demand use of a very low calorie diet. A randomized 2-year clinical trial. J Intern med. 2003;253:463-71.

[35] Wing R, et al. Year-long weight loss treatment for obese patients with type II diabetes. Does including an intermittent very-low-calorie diet improve outcome? AM J Med. 1994;97:354-62.

[36] Wing R, Jeffery R. Prescribed “breaks” as a means to disrupt weight control efforts. Obes Res. 2003;11:287-91.

[37] Cioffi I, et al. Intermittent versus continuous energy restriction on weight loss and cardiometabolic outcomes: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Transl Med. 2018;16:371.

[38] Varady K, et al. Comparison of effects of diet versus exercise weight loss regimens on LDL and HDL particle size in obese adults. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:119.

[39] Harvie M, et al. The effect of intermittent energy and carbohydrate restriction v. daily energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers in overweight women. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1534.

[40] Coutinho S, et al. Compensatory mechanisms activated with intermittent energy restriction: a randomized control trial. Clin Nutr. 2018;37:815.

[41] Barnosky A, et al. Intermittent fasting vs. daily calorie restriction for type 2 diabetes prevention: a review of human findings. Transl Res. 2014;164:302.

[42] Seimon R, et al. Do intermittent diets provide physiological benefits over continuous diets for weight loss? A systematic review of clinical trials. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;418:153.

[43] Anton S, et al. Flipping the switch: understanding and applying the health benefits of fasting. Obesity. 2018;26;254.

[44] Moro T, et al. Effects of eight weeks of time-restricted feeding (16/8) on basal metabolism, maximal strength, body composition, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk factors in resistance-trained males. J Transl Med. 2016 Oct 13;14(1):290.

[45] Sutton E, et al. Early time-restricted feeding improves insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, and oxidative stress even without weight loss in men with prediabetes. Cell Metab. 2018 June;27:1212-21.

[46] Hirsh S, et al. Avoiding holiday season weight gain with nutrient-supported intermittent energy restriction: a pilot study. J Nutr Sci. 2019;8:e11.

The information provided is for educational purposes only. Consult your physician or healthcare provider if you have specific questions before instituting any changes in your daily lifestyle including changes in diet, exercise, and supplement use.

Share this post

Related posts

Vitamin C to Ease the Pain

Nutritional support for acute, chronic, surgical, and cancer-related pain Part 1 in our three-part series on vitamin C, pain, and opioid addiction. What do humans have in common with other primates, bats, and guinea pigs? (No, not a love of cheese!) We cannot make L-gulonolactone oxidase (GLO), the enzyme needed to biosynthesize ascorbate (vitamin…

DHEA for Bones, Brains, and in the Bedroom

The anti-aging perks of the dietary supplement DHEA Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfated form, DHEA-S, are the most abundant steroid hormones in the human body.1 DHEA is produced from cholesterol in the adrenal glands, brain, ovaries, and testes, and is then converted into the major sex hormones estrogen and testosterone. DHEA levels decline dramatically…

Probiotics and the Human Microbiome: Beyond the Gut

Dr. Don Brown, ND, discusses cutting edge research on the use of probiotics Biography: Naturopathic physician Dr. Donald Brown is one of the leading authorities in the U.S. on evidence-based herbal medicine and the safety and efficacy of nutritional supplements and probiotics. He currently serves as the Director of Natural Product Research Consultants in…

Vitamin C for Mood and Addiction

How ascorbic acid soothes the brain Beyond immune support Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is best known for its immune-enhancing effects – from reducing the severity and duration of the common cold,[1] to supporting the health of individuals with HIV/AIDS,[2] to reducing the histamine response seen in allergies and asthma,[3],[4],[5] to even potentially reducing the…

Connective Tissue Support, from Skin to Joint

How connective tissue nutrients support many aspects of health Many of us have experienced the tough, rubbery cartilage found at the end of a chicken drumstick and thought little, if anything, of its nutritive value. Yet the nutrients found in cartilage – namely collagen and proteoglycans – have much to offer us with respect…

Say Yes to NO: Nitric Oxide

Support for heart health, sexual performance, and beyond Nitric oxide (NO) is a tiny gas molecule produced in the blood vessels, nerves, and immune cells. Best known for its role in maintaining blood pressure, NO also mediates penile erections, supports healthy blood flow to the brain, enhances muscle oxygen use during exercise, and helps…

Categories

- Botanicals (56)

- GI Health (53)

- Healthy Aging (121)

- Immune Support (39)

- In The News (39)

- Kids Health (21)

- Stress and Relaxation (50)

- Uncategorized (1)

- Video (9)

- Vitamins & Minerals (51)