Share this post

The importance of amino acids

Do you have strong muscles? If the answer is yes, then you have a greater than average chance of living a healthy and happy life. Being physically strong helps us feel and look healthy, and carry out our everyday activities with ease. Muscle strength also helps reduce the chance of frailty and falls in later life.[1],[2],[3]

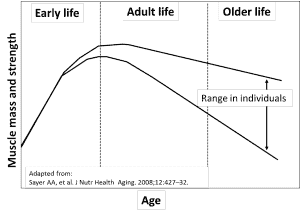

Muscle strength peaks when people are in their 20s and then begins a downhill slide, as depicted in the graph below.[4],[5],[6],[7]

Numerous studies show that individuals at the low end of the strength range have an inferior quality of life and a higher mortality rate from all causes.[8],[9],[10],[11]

Low muscle strength is associated with a higher risk of metabolic syndrome, heart disease, depression, and Alzheimer’s disease.

In fact, the effect of low muscle strength on mortality at any age is as great as the effect of established risk factors such as obesity or high blood pressure.[11] Low muscle strength is associated with a higher risk of metabolic syndrome,[12] heart disease,[13] depression,[14] and Alzheimer’s disease.[15]

If we can stay in the upper range of muscle strength throughout life, we have a good chance of avoiding many age-related disabilities. Let’s examine how exercise and nutrition can help.

Resistance training increases muscle strength at all ages

Regular physical activity has been proven to slow the age-related loss of muscle mass and strength.[16] According to the World Health Organization, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the American College of Sports Medicine, adults of all ages should do two kinds of regular exercise: (1) muscle-strengthening exercises involving the major muscle groups at least two days a week; and (2) at least 150 minutes (two and a half hours) of moderate-intensity aerobic activity throughout the week.[17],[18],[19],[20]

Resistance training (RT) in particular produces a significant increase in muscle strength in healthy adults of all ages.[18],[21],[22] In one study, even nursing home residents in their 90’s experienced an average 174% gain in muscle strength after eight weeks of RT.[23]

Adequate dietary protein is essential for strong muscles

Inadequate dietary protein intake is a major contributor to muscle atrophy.[24] Conversely, adequate protein nutrition – especially in combination with RT – helps maintain muscle strength throughout life.[2] Protein supplementation boosts the response of skeletal muscle to RT, and RT allows more of the ingested amino acids to be used by the muscles.[2],[21],[25],[26],[27],[28]

Muscle comprises about 30 to 40 percent of the body weight of adults.[29] About 20% of muscle is comprised of protein, which is made from 20 different amino acids. Nine of these amino acids — histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine — are not synthesized by mammals and therefore must be obtained from the diet. For this reason, they are known as essential amino acids (EAAs).[30]

The other 11 amino acids are called “nonessential amino acids” (NEAAs) because they can be made within the body. Some or all NEAAs may be conditionally essential, however, as discussed below. Muscle protein synthesis is suboptimal if any of the EAAs are missing, whereas a shortage of NEAAs can sometimes be compensated by increased NEAA synthesis.[31]

How much protein is needed?

The American Council on Sports Medicine says: “When trying to build muscle, think quality, quantity and timing. Aim to eat 20 to 30 grams of high-quality protein foods within 2 hours of exercise to help muscle protein synthesis.”[32]

Older individuals may require larger amounts – between 30 and 40 grams of protein at each of three meals per day – as compared to younger adults.[28],[33],[34],[35] This is because aged muscles do not respond as well to EAAs, a phenomenon known as anabolic resistance.[3] Hypochlorhydria, a condition of having lower levels of stomach acid than one should, also is more common with increasing age and adversely affects the body’s ability to absorb protein and other nutrients.[36]

Individuals in their 70s with the highest protein intakes lost about 40% less muscle mass than those in the lowest protein bracket.

Increasing protein intake can overcome both of these problems.[3] A three-year study of individuals in their 70s showed that those with the highest protein intakes lost about 40% less muscle mass than those in the lowest protein bracket.[37] (High protein intake isn’t for everyone, though – individuals with some forms of chronic kidney disease are generally advised to eat a diet with lower amounts of protein, so check with your doctor before embarking on a high protein diet.)

High-quality (“complete”) protein foods, which are needed for optimal muscle protein synthesis, contain all nine EAAs needed to build muscle. Complete protein foods include dairy products, eggs, meats, poultry, and seafood. Except for soy,[38] plant-based protein sources are often missing important EAAs such as lysine, methionine, isoleucine, threonine, and/or tryptophan.[39],[40] The intakes of all dietary amino acids are nearly 50% lower in vegans than in meat-eaters.[41]

For reasons of dietary choice, appetite, and logistics, it may be difficult for individuals to consume large amounts of complete protein at every meal. Amino acid supplementation has been suggested to help avoid a shortage of EAAs.[42],[43],[44],[45]

Our muscles respond to essential amino acids!

Our muscles perk up at the sight of EAAs! Muscle protein synthesis (MPS) increases by 30 to 100% in response to a meal that contains EAAs.[46] EAAs stimulate MPS at all ages.[47] Supplementation with a large dose of EAAs (12 grams daily) was shown to improve handgrip strength and six-minute walking distance (a measure of physical function) in elderly individuals after only three months.[48]

The branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) – leucine, isoleucine, and valine – are the most abundant EAAs.[49] It has been discovered that leucine directly stimulates MPS by activating key enzymes in the MPS pathway.[50],[51]

It is necessary to ingest all nine EAAs at the same time to boost muscle protein synthesis. Leucine or BCAA supplements alone are not effective unless they are added to a protein meal.

Whey protein is high in BCAAs and has superior muscle-building properties as compared to soy or casein.[52] However, studies have shown supplying the body with EAAs in their free format is even more effective than whey protein – a 3 gram dose of EAAs, providing 1.2 grams of leucine, produced the same MPS effect as 20 grams of whey protein.[53],[54] In another study, 1.5 grams of EAAs, which provided only 0.6 grams of leucine, was also effective.[54] However, it is necessary to ingest all nine EAAs at the same time to boost MPS; leucine or BCAA supplements alone do not appear to be effective unless they are added to a protein meal.[45],[46],[55],[56],[57]

Compared to intact proteins or hydrolyzed formulas, free amino acid supplements have the advantage of being hypoallergenic, because they do not contain peptides that can be recognized by immune cells.[58] Thus free amino acids may be helpful for individuals who react to dairy proteins and other proteins like those found in egg or soy.[59],[60],[61] Free amino acids are not bound in proteins that need to be broken down by gastric acids in the stomach and digestive enzymes from the pancreas, so for the many individuals with pancreatic insufficiency, hypochlorhydria, or on acid suppression therapies they can be absorbed much better.

Do we need “non-essential” amino acids?

The NEAAs are alanine, arginine, asparagine, aspartate, cysteine, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, and tyrosine. These amino acids are synthesized in the body, but not always in sufficient amounts.[62],[63] Taurine, an amino acid that is not used for MPS, nevertheless helps prevent the muscle damage seen with exercise.[64],[65] It also enhances bile acid production,[66] and helps protect against high blood pressure.[67],[68] Vegans, however, have only negligible intakes of taurine, as taurine is found only in animal foods.[69]

Among the other NEAAs, cysteine and glycine deficiencies can impede glutathione synthesis, especially in older individuals or in those on low-protein diets.[70],[71],[72] Glycine, arginine, and proline help support collagen biosynthesis under conditions of physical stress or injury;[73],[74] and glutamine plays an important role in intestinal barrier function.[75] Because of the body’s need for these and some of the other NEAAs at times of stress or illness they are often termed “conditionally essential amino acids.” As stated in a 2017 review, “Extensive studies indicate that animals and humans cannot adequately synthesize NEAAs to meet optimal metabolic and functional needs under either normal or stress conditions.”[62]

Summary

A combination of resistance training and adequate intake of high-quality dietary protein is recommended to forestall muscle atrophy and increasing disability with age.[76] If it’s not possible to obtain a sufficient amount of complete protein at every meal, free amino acid supplementation may help. Look for a supplement that contains all 9 EAAs, along with other key amino acids such as arginine, cysteine, glutamine, glycine, proline, and taurine.

Click here to see References[1] Trombetti A, et al. Age-associated declines in muscle mass, strength, power, and physical performance: impact on fear of falling and quality of life. Osteoporos Int. 2016 Feb;27(2):463-71.

[2] Deutz NE, et al. Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: recommendations from the ESPEN Expert Group. Clin Nutr. 2014 Dec;33(6):929-36.

[3] Volpi E, et al. Is the optimal level of protein intake for older adults greater than the recommended dietary allowance? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013 Jun;68(6):677-81.

[4] Keller K, Engelhardt M. Strength and muscle mass loss with aging process. Age and strength loss. Musc Lig Tend J. 2014 Feb 24;3(4):346-50.

[5] van Haehling S, et al. From muscle wasting to sarcopenia and myopenia: update 2012. J Cachex Sarcop Musc. 2012 Dec;3(4):213-7.

[6] Westerståhl M, et al. Longitudinal changes in physical capacity from adolescence to middle age in men and women. Sci Rep. 2018 Oct 3;8(1):14767.

[7] Sayer AA, et al. The developmental origins of sarcopenia. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008 Aug-Sep;12(7):427-32.

[8] Sasaki H, et al. Grip strength predicts cause-specific mortality in middle-aged and elderly persons. Am J Med. 2007 Apr;120(4):337-42.

[9] Prasitsiriphon O, Pothisiri W. Associations of grip strength and change in grip strength with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a European older population. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2018 Apr 20;12:1179546818771894.

[10] Musalek C, Kirchengast S. Grip strength as an indicator of health-related quality of life in old age – a pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Nov 24;14(12):1447.

[11] Ortega FB, et al. Muscular strength in male adolescents and premature death: cohort study of one million participants. BMJ. 2012 Nov 20;345:e7279.

[12] Jurca R, et al. Association of muscular strength with incidence of metabolic syndrome in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005 Nov;37(11):1849-55.

[13] Wu Y, et al. Association of grip strength with risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer in community-dwelling populations: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017 Jun 1;18(6):551.

[14] Lee MR, et al. The association between muscular strength and depression in Korean adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the sixth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VI) 2014. BMC Public Health. 2018 Sep 15;18(1):1123.

[15] Camargo EC, et al. Association of physical function with clinical and subclinical brain disease: the Framingham Offspring Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016 Jul 14;53(4):1597-608.

[16] Zampieri S, et al. Lifelong physical exercise delays age-associated skeletal muscle decline. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015 Feb;70(2):163-73.

[17] World Health Organization (WHO). Physical activity and adults: Recommended levels of physical activity for adults aged 18 – 64 years [Internet]; 2011 [cited 2019 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_adults/en/

[18] World Health Organization (WHO). Physical activity and older adults: recommended levels of physical activity for adults aged 65 and above. 2011 [cited 2019 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_olderadults/en/

[19] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 2]. Available from: https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/

[20] Garber CE, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 Jul;43(7):1334-59.

[21] Morton RW, et al. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Mar;52(6):376-84.

[22] Nilwik R, et al. The decline in skeletal muscle mass with aging is mainly attributed to a reduction in type II muscle fiber size. Exp Gerontol. 2013 May;48(5):492-8.

[23] Fiatarone MA, et al. High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians. Effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA. 1990 Jun 13;263(22):3029-34.

[24] Cruz-Jentoft AJ, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on sarcopenia in older people. Age Ageing. 2010 Jul;39(4):412-23.

[25] Yang Y, et al. Resistance exercise enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis with graded intakes of whey protein in older men. Br J Nutr. 2012 Nov 28;108(10):1780-8.

[26] Pennings B, et al. Exercising before protein intake allows for greater use of dietary protein-derived amino acids for de novo muscle protein synthesis in both young and elderly men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Feb;93(2):322-31.

[27] Bowen TS, et al. Skeletal muscle wasting in cachexia and sarcopenia: molecular pathophysiology and impact of exercise training. J Cach Sarcop Musc. 2015 Sep;6(3):197-207.

[28] Holwerda AM, et al. Dose-dependent increases in whole-body net protein balance and dietary protein-derived amino acid incorporation into myofibrillar protein during recovery from resistance exercise in older men. J Nutr. 2019 Feb 4:1-10.

[29] Janssen I, et al. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18-88 yr. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000 Jul;89(1):81-8.

[30] Watford M, Wu G. Protein. Adv Nutr. 2018 Sep 1;9(5):651-3.

[31] Volpi E, et al. Essential amino acids are primarily responsible for the amino acid stimulation of muscle protein anabolism in healthy elderly adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Aug;78(2):250-8.

[32] Lewis-McCormick I, Bassler R. Industry-presented blog: half a dozen nutrition myths debunked [Internet]. American College of Sports Medicine blog; 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 2]. https://www.acsm.org/blog-detail/acsm-certified-blog/2018/01/18/half-a-dozen-nutrition-myths-debunked. Accessed February 2, 2019.

[33] Moore DR, et al. Protein ingestion to stimulate myofibrillar protein synthesis requires greater relative protein intakes in healthy older versus younger men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015 Jan;70(1):57-62.

[34] Paddon-Jones D, et al. Amino acid ingestion improves muscle protein synthesis in the young and elderly. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Mar;286(3):E321-8.

[35] Witard OC, et al. Growing older with health and vitality: a nexus of physical activity, exercise and nutrition. Biogerontology. 2016 Jun;17(3):529-46.

[36] Holt PR, et al. Causes and consequences of hypochlorhydria in the elderly. Dig Dis Sci. 1989 Jun;34(6):933-7.

[37] Houston DK, et al. Dietary protein intake is associated with lean mass change in older, community-dwelling adults: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Jan;87(1):150-5.

[38] Michelfelder AJ. Soy: a complete source of protein. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Jan 1;79(1):43-7.

[39] Rogerson D. Vegan diets: practical advice for athletes and exercisers. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017 Sep 13;14:36.

[40] Gorissen SHM, et al. Protein content and amino acid composition of commercially available plant-based protein isolates. Amino Acids. 2018 Dec;50(12):1685-95.

[41] Schmidt JA, et al. Plasma concentrations and intakes of amino acids in male meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans: a cross-sectional analysis in the EPIC-Oxford cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016 Mar;70(3):306-12.

[42] Drummond MJ. A practical dietary strategy to maximize the anabolic response to protein in aging muscle. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015 Jan;70(1):55-6.

[43] Churchward-Venne TA, et al. Leucine supplementation of a low-protein mixed macronutrient beverage enhances myofibrillar protein synthesis in young men: a double-blind, randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014 Feb;99(2):276-86.

[44] Dickinson JM, et al. Leucine-enriched amino acid ingestion after resistance exercise prolongs myofibrillar protein synthesis and amino acid transporter expression in older men. J Nutr. 2014 Nov;144(11):1694-702.

[45] Wall BT, et al. Leucine co-ingestion improves post-prandial muscle protein accretion in elderly men. Clin Nutr. 2013 Jun;32(3):412-9.

[46] Jäger R, et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017 Jun 20;14:20.

[47] Ferrando AA, et al. EAA supplementation to increase nitrogen intake improves muscle function during bed rest in the elderly. Clin Nutr. 2010 Feb;29(1):18-23.

[48] Scognamiglio R, et al. Oral amino acids in elderly subjects: effect on myocardial function and walking capacity. Gerontology. 2005 Sep-Oct;51(5):302-8.

[49] Nie C, et al. Branched chain amino acids: beyond nutrition metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Mar 23;19(4):954.

[50] Jewell JL, et al. Amino acid signaling upstream of mTOR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013 Mar;14(3):133-9.

[51] Blomstrand E, et al. Branched-chain amino acids activate key enzymes in protein synthesis after physical exercise. J Nutr. 2006 Jan;136(1 Suppl):269S-73S.

[52] Tang JE, et al. Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in young men. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009 Sep;107(3):987-92.

[53] Bukhari SS, et al. Intake of low-dose leucine-rich essential amino acids stimulates muscle anabolism equivalently to bolus whey protein in older women at rest and after exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Jun 15;308(12):E1056-65.

[54] Wilkinson DJ, et al. Effects of leucine-enriched essential amino acid and whey protein bolus dosing upon skeletal muscle protein synthesis at rest and after exercise in older women. Clin Nutr. 2018 Dec;37(6 Pt A):2011-21.

[55] Kobayashi H. Age-related sarcopenia and amino acid nutrition. J Phys Fit and Sports Med. 2013 Nov 25;2(4):401-7.

[56] Cheng H, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of protein and amino acid supplements in older adults with acute or chronic conditions. Br J Nutr. 2018 Mar;119(5):527-42.

[57] Wolfe RR. Branched-chain amino acids and muscle protein synthesis in humans: myth or reality? J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017 Aug 22;14:30.

[58] Andreae D, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. The effect of infant allergen/immunogen exposure on long-term health. Early Nutrition and Long-Term Health. 2017;131-73.

[59] Sousa MJCS, et al. Bodybuilding protein supplements and cow’s milk allergy in adult. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018 Jan;50(1):42-4.

[60] Hill DJ, et al. The efficacy of amino acid-based formulas in relieving the symptoms of cow’s milk allergy: a systematic review. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007 Jun;37(6):808-22.

[61] Lam HY, et al. Cow’s milk allergy in adults is rare but severe: both casein and whey proteins are involved. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008 Jun;38(6):995-1002.

[62] Wu G. Dietary requirements of synthesizable amino acids by animals: a paradigm shift in protein nutrition. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2014 Jun 14;5(1):34.

[63] Hou Y, Wu G. Nutritionally nonessential amino acids: a misnomer in nutritional sciences. Adv Nutr. 2017 Jan 17;8(1):137-9.

[64] DeCarvalho FG, et al. Taurine: a potential ergogenic aid for preventing muscle damage and protein catabolism and decreasing oxidative stress produced by endurance exercise. Front Physiol. 2017 Sep 20;8:710.

[65] Scicchitano BM, Sica G. The beneficial effects of taurine to counteract sarcopenia. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2018;19(7):673-80.

[66] Murakami S, et al. Taurine ameliorates cholesterol metabolism by stimulating bile acid production in high-cholesterol-fed rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2016 Mar;43(3):372-8.

[67] Waldron M, et al. the effects of oral taurine on resting blood pressure in humans: a meta-analysis. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018 Jul 13;20(9):81.

[68] Wojcik OP, et al. Serum taurine and risk of coronary heart disease: a prospective, nested case-control study. Eur J Nutr. 2013 Feb;52(1):169-78.

[69] Laidlaw SA, et al. Plasma and urine taurine levels in vegans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988 Apr;47(4):660-3.

[70] McCarty MF, DiNicolantonio JJ. An increased need for dietary cysteine in support of glutathione synthesis may underlie the increased risk for mortality associated with low protein intake in the elderly. Age (Dordr). 2015 Oct;37(5):96.

[71] Sekhar RV, et al. Deficient synthesis of glutathione underlies oxidative stress in aging and can be corrected by dietary cysteine and glycine supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Sep;94(3):847-53.

[72] Razak MA, et al. Multifarious beneficial effect of nonessential amino acid, glycine: a review. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1716701.

[73] Shaw G, et al. Vitamin C-enriched gelatin supplementation before intermittent activity augments collagen synthesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017 Jan;105(1):136-43.

[74] Meesters DM, et al. Malnutrition and fracture healing: are specific deficiencies in amino acids important in nonunion development? Nutrients. 2018 Oct 31;10(11):1597.

[75] Wang B, et al. Glutamine and intestinal barrier function. Amino Acids. 2015 Oct;47(10):2143-54.

[76] Mendonça N, et al. Protein intake and disability trajectories in very old adults: the Newcastle 85+ Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019 Jan;67(1):50-56.

The information provided is for educational purposes only. Consult your physician or healthcare provider if you have specific questions before instituting any changes in your daily lifestyle including changes in diet, exercise, and supplement use.

Share this post

Marina MacDonald, MS, PhD

Related posts

Are You Nitric Oxide Deficient? Part 2 of 2

Dr. Nathan Bryan, Ph.D., on nitric oxide, the peroxynitrite issue, and nutritional tools that may help improve nitric oxide production Biography: Nathan S. Bryan, Ph.D., is an international leader in molecular medicine and nitric oxide biochemistry. Specifically, Dr. Bryan was the first to describe nitrite and nitrate as indispensable nutrients required for optimal cardiovascular…

Vitamin K2 for Strong Bones and Flexible Arteries

The vitamin that sends calcium where it’s needed. Calcium is an important mineral for bone health, muscle contraction, nerve signaling, and blood clotting.[1],[2] But more calcium isn’t necessarily better: If calcium deposits in the walls of arteries, it can cause the blood vessels to become stiff, thus increasing the risk of heart disease. [3],[4],[5]…

NAD+: Health or Hype?

What the research says about nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide What is NAD+? NAD+, or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, is a coenzyme – or enzyme “helper” that supports important reactions in the body. NAD+ is needed to help turn nutrients into energy, and is thus a key player in mitochondrial health. NAD+ also helps repair damaged…

Turmeric: A Golden Remedy for Musculoskeletal Health

Curcuminoids, the famous active compounds from turmeric, deliver benefits for joint health and exercise recovery Liquid gold. Golden milk. That brilliant saffron-hued spice. We hear a lot about turmeric these days—also known as Curcuma longa—a member of the ginger family, and native of Southeast Asia.[1] Valued for its brilliant hue and distinctive spicy-bitter flavor,…

The Beauty of “Beasty Bits”

Glandular products for advanced support What is Glandular Therapy? When it comes to the matter of the endocrine glands and the hormones they produce, modern medicine has done well in isolating and synthesizing in the lab the very hormones we produce in our bodies. Whether it’s the insulin injected by a Type I diabetic,…

Feed Your Brain, Part 2 of 2

Cutting edge science for cognitive enhancement There has been an astonishing increase in average life expectancy over the last 100 years. Each generation is living longer, and our intelligence is steadily rising. That means there is a high premium on maintaining a cognitive edge—one that lasts for our entire lifespan. Science is now discovering…

Categories

- Botanicals (56)

- GI Health (53)

- Healthy Aging (121)

- Immune Support (39)

- In The News (39)

- Kids Health (21)

- Stress and Relaxation (50)

- Uncategorized (1)

- Video (9)

- Vitamins & Minerals (51)